It is no secret China’s communist leaders do not like having their human rights credentials questioned, but based on a response from Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Canada Wednesday, it apparently is a topic that should not be brought up.

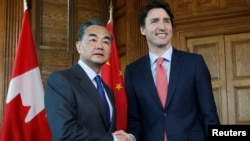

Speaking with reporters at the end of a high-profile visit to Canada, at a time when the two countries are said to be ushering in a new golden era of relations, Wang lashed out at a journalist, scolding her for asking a question about his country's human rights record.

Arrogant and unacceptable

In his response, Wang asked if the reporter had ever even been to China and argued that her remarks were full of “arrogance” and “prejudice” and totally “unacceptable.”

"I would like to suggest to you that please don't ask questions in such an irresponsible manner,” Wang said. “We welcome goodwill suggestions but we reject groundless or unwarranted accusations."

Wang went on to raise an argument his authoritarian government frequently uses when such concerns are raised, pointing out that hundreds of millions have been lifted out of poverty and that China’s constitution guarantees the protection and promotion of human rights.

"Let me tell you who best understands China’s human rights situation," he said. "It is not you, but the Chinese people. You have no right to speak about China’s human rights. It is the Chinese people who have the right to speak about China’s human rights."

Reality check

What do the Chinese people know and have to say about their human rights situation?

Plenty, but those who do, usually end up in the crosshairs of China’s ever expanding security apparatus.

Since President Xi Jinping rose to power more than three years ago, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an advocacy group, has documented more than 2,000 rights defenders who have been detained, a significant increase from the past, said one of its researchers, Frances Eve.

“Within this group of 2,000 individuals who are Chinese citizens who want to talk about human rights and, according to the foreign minister, are the only ones allowed to, they’ve been denied that right,” Eve said.

Eve notes that those who have been detained include human rights lawyers, members of the New Citizens Movement who have called for government transparency and rule of law, and individual Chinese citizens expressing their support for the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, among others.

“These are not particularly controversial areas, not particularly challenging the overriding supremacy of the Communist Party,” she said, adding that in each case they have been detained and denied their right to talk about the human rights situation in their country, despite guarantees clearly outlined in the constitution.

“And that just shows how bad the situation has become,” Eve said.

Repression spreading

The repression is not limited to the mainland. Critics in China and Western governments have raised concerns about Beijing’s recent detentions of booksellers in Hong Kong — which the reporter raised in her question — and arrest of activists in Thailand and Myanmar.

The government prevents activists from traveling abroad to speak about China’s human rights.

Cao Shunli, a Chinese activist who was trying to participate in China’s human rights review at the United Nations, was barred from traveling to Geneva, detained and denied medical treatment. She died in March of 2014.

“The government has a concerted policy to prevent Chinese citizens from commenting on the human rights situation in China, trying to control this narrative,” Eve said.

Terror and suffocation

This weekend marks the 27th anniversary of China’s bloody Tiananmen Square crackdown on pro-democracy protesters. No one knows just how many died on the night of June 3-4, 1989, but estimates from rights groups and witnesses put the numbers in the hundreds if not thousands.

Since then, the parents of those who died — known as The Tiananmen Mothers — have been asking for three simple things: truth, accountability and compensation.

The government has repeatedly denied and ignored that request.

On Wednesday, the group issued a statement that talked about what their experience has been like as they have sought redress, describing the past 27 years as that of “[state] terror and suffocation.”

“For 27 years, the police have been the ones who have dealt with us. For 27 years, they have also been our frequent visitors at home,” the statement said. “We the victims’ families are eavesdropped and surveilled upon by the police; we are followed or even detained, and our computers searched and confiscated.”

Members of the group note that the surveillance and scrutiny intensifies around special dates, particularly the anniversary.

In their statement, they added that visits to the founder of the group, 79-year-old former university professor Ding Zilin, have been restricted and that only one individual may visit her at a time, only after receiving approval from Beijing’s Public Security Bureau.